Femia > Health Library > Pregnancy > Giving birth > Understanding early decelerations in fetal heart rate monitoring

Understanding early decelerations in fetal heart rate monitoring

- Updated

- Published

The slowing down of your baby’s heart rate during contractions is known as decelerations. Early decelerations start and end with a contraction. Early decels are thought to be caused by fetal head compression during a contraction. These are usually benign and do not pose any risk to the baby.

While you are in labor and feeling the effects of each contraction, so is your baby. To monitor how your contractions are affecting your baby, doctors will chart the fetal heart rate.

While this is happening, it’s normal to see a few occasional variations in the heart rate either with or following the contractions. Decreases in fetal heart rate coinciding with the start and end of a contraction are called early decelerations.

Early decels are often not a cause of concern. However, prolonged and recurrent decreases in heart rate could pose a risk to your baby and require medical intervention. This makes understanding the different types of decelerations important for expectant parents and their healthcare providers.

Track your symptoms with Femia and get tailored

health advice right on your phone

What are early decelerations?

Decelerations are used to describe a decrease in fetal heart rate during labor, specifically with contractions.

Fetal heart rate is the least invasive method to assess how your baby is progressing through labor along with you and track its responses to changes in the uterine environment, like contractions. A contraction can limit the oxygen supply to your baby, triggering cardiac and nervous system responses to compensate. These variations are picked up when charting your baby’s heart rate during labor.

Early decelerations are used to describe the decrease in fetal heart rate coinciding with the beginning of a new contraction. Early decels also end along with the contraction, the lowest point of the deceleration coincides with the peak of a contraction. For a deceleration to be classified as an early deceleration, there must be at least 30 seconds from the onset of the deceleration to its lowest point (nadir), and then it returns to baseline.

👉Find out more: Twin pregnancy belly week by week: What to expect

Significance of early decelerations

While decelerations can indicate fetal distress due to limited blood supply or decreased oxygen in some situations, early decelerations are usually benign. They signify brief fetal head compressions with contractions.

Early decelerations can also be a reassuring sign that your labor is progressing, indicating the descent of the fetal head into the birth canal. However, early decels that are recurrent, intense, and last for a long time may be a sign to your doctor that it’s time to start pushing.

Early vs late decelerations

Decelerations are divided into three categories: early, late, and variable. The early and late decelerations describe a decrease in fetal heart rate along with a coinciding contraction.

Early decelerations, as described above, start and end with a contraction. This means the lowest heart rate is noted with the peak of the contraction, following which the heart rate goes back to its normal range.

Late decelerations, on the other hand, either start at the peak of a contraction or after a contraction ends. A single late deceleration may not be a cause for immediate concern as long as the baby’s heart rate comes back to a normal range relatively quickly. However, persistent late deceleration could indicate insufficient blood flow through the placenta, limiting oxygen to the fetus. In severe cases, these low levels of oxygen (hypoxia) can result in acidosis, a condition in which there is too much acid in the body fluids.

With early decelerations, fetal heart rate decreases don’t cause injury, as they signal the momentary compression of your baby’s head passing through the pelvis. On the other hand, late decelerations indicate a more serious uteroplacental insufficiency, which occurs when the placenta does not develop properly, or is damaged. However, either deceleration, when recurrent (recorded 50% of the time in 20 minutes), warrants medical interventions, which can include emergent delivery.

Causes of early decelerations

Early decels occur due to fetal head compressions during contractions, not from low levels of oxygen (hypoxia). Due to the compression, there is a decrease in blood flow to the carotid arteries, causing decreased oxygen to only the central nervous system. As a response to the increased pressure around the brain (intracranial pressure) from the compression, the vagal autonomic system is activated, reducing fetal heart rate.

A review of medical literature has shown that while head compression can result in occasional decelerations during a normal delivery, fetal anatomical adaptations prevent significant injury during these compressions.

It is reassuring to observe occasional early decelerations as your labor progresses, as they show that your baby is moving slowly into the birth canal as your cervix dilates.

Track your symptoms with Femia and get tailored

health advice right on your phone

Why does baby heart rate drop during contractions

As described above, your baby’s heart rate is deeply connected to various physiological functions taking place during labor.

With early decelerations, the decrease in heart rate is from vagal response that occur when the vagus nerve is stimulated, to the increased pressure around the brain resulting from the head compression during a contraction. In most cases, this doesn’t result in fetal injury and suggests the progression of labor.

With late decelerations, a drop in fetal heart rate occurs either at the end or after a contraction. This is a response to decreased placental blood flow leading to fetal hypoxia during the contraction. A persistent lack of oxygen can cause acid levels to increase, which can show up as intense and recurrent late decelerations.

As your labor progresses, it is common to record an occasional drop in your baby’s heart rate for various reasons. But, as long as it is not frequent or a big drop, it’s usually not a cause for concern, that should be monitored closely.

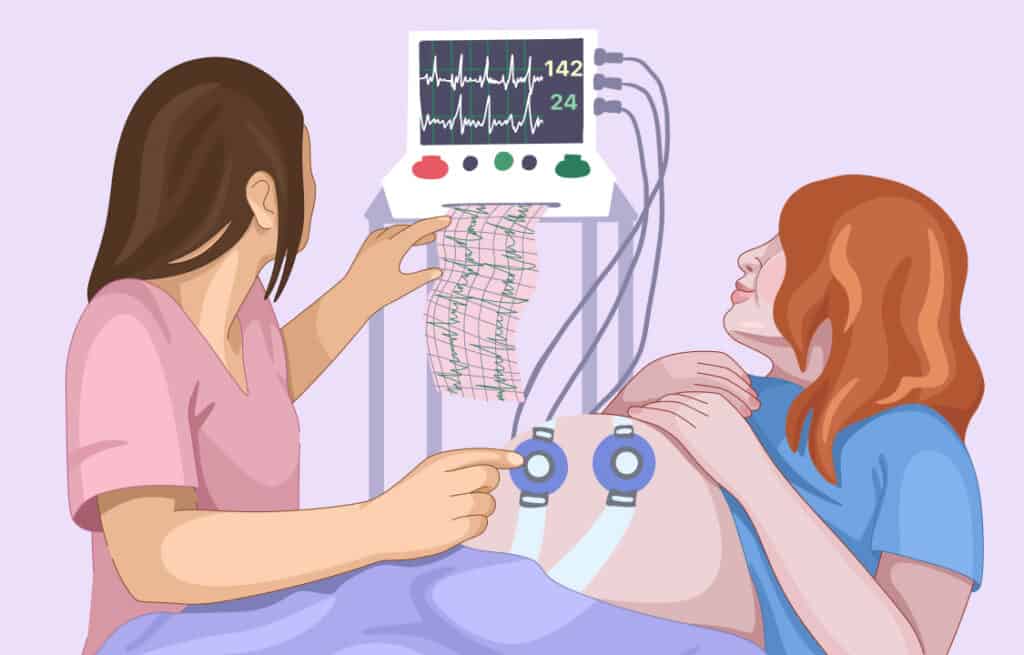

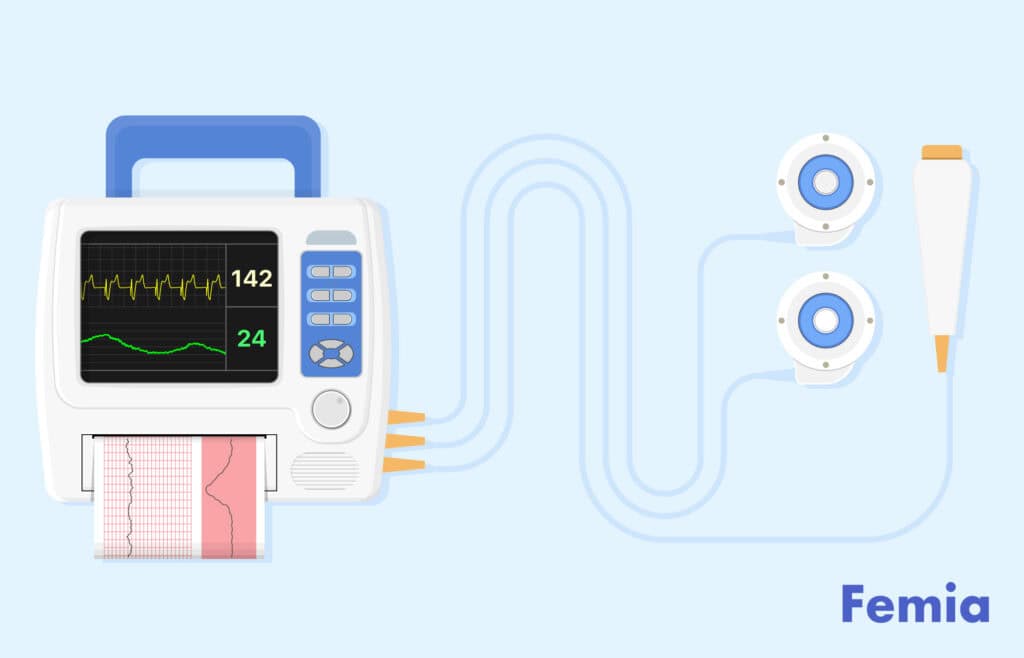

Monitoring and managing early decelerations

Fetal heart rate monitoring is a continuous process throughout labor. The most common way to measure this is through an external Doppler ultrasound, which will be placed on your abdomen. In some cases, if your doctor cannot get a proper reading externally, an internal device will be placed, often on your baby’s scalp. This is done only if your amniotic sac has ruptured.

With continuous monitoring, your doctor can record recurrent early decels and take actionable steps to prevent any complications during labor and delivery. The first step would be to identify the underlying cause for the decelerations.

Recurrent decelerations can cause a decrease in oxygen supply to your baby. To help increase oxygen, your doctor will often suggest you make a few positional changes that might help. One position is moving to your left side with your knee to your chest. Once in this position, the fetal heart rate will be observed over time to see if there is any improvement. For some, movement to the right side might help as well, as it relieves pressure from the vena cava, your body’s largest vein.

With persistent decelerations, your doctor may consider some additional management efforts, which could include initiating maternal oxygen, IV fluids, and reducing the frequency of contractions to allow for fetal recovery between them.

Rest assured, early decelerations are rarely concerning, requiring little to no intervention other than close monitoring throughout labor.

Questions from the Femia community

Are early decelerations always benign, or should I be concerned if they are seen during labor?

Early decelerations are usually not indicative of fetal distress. These decelerations start with and end with a contraction and are just a sign of fetal head compression as your baby is passing through your uterus into the birth canal. However, early decelerations that are recurrent, intense, or change patterns (to late or variable) will prompt your healthcare provider to take the appropriate steps to prevent associated complications.

What should I do if I notice late decelerations instead of early decelerations during labor?

The healthcare provider taking care of you during your labor and delivery will regularly monitor your fetal heart rate. This will be done routinely every 15–30 minutes, more often if there are concerning changes. Continuous monitoring helps to identify changes in early decelerations if they occure to late decelerations promptly, so appropriate medical interventions can be initiated in time. If you notice any physical discomfort or distress during labor, be sure to bring it to the attention of your healthcare providers.

The bottom line

Early decelerations indicate a drop in your baby’s heart rate along with your contractions. Early decels happen because of fetal head compression taking place during a contraction. Early decelerations are normal, and labor often progresses with no danger to either you or your baby. Your doctor will regularly monitor fetal heart rate for fluctuations, changes in patterns, and recurrences of decelerations, to prevent any complications early.

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). “Fetal Heart Rate Classifications.” Addendum to Intrapartum Care: Care for Healthy Women and Babies – NCBI Bookshelf, 1 Feb. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK550641.

- Xodo, Serena, and Ambrogio P. Londero. “Is It Time to Redefine Fetal Decelerations in Cardiotocography?” Journal of Personalized Medicine, vol. 12, no. 10, Sept. 2022, p. 1552. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12101552.

- Robinson, Barrett. “A Review of NICHD Standardized Nomenclature for Cardiotocography: The Importance of Speaking a Common Language When Describing Electronic Fetal Monitoring.” PubMed Central (PMC), 1 Jan. 2008, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2505172.

- Mocsáry, P., et al. “Relationship Between Fetal Intracranial Pressure and Fetal Heart Rate During Labor.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 106, no. 3, Feb. 1970, pp. 407–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(70)90367-4.

- Lear, Christopher A., et al. “Fetal Defenses Against Intrapartum Head Compression—implications for Intrapartum Decelerations and Hypoxic-ischemic Injury.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 228, no. 5, May 2023, pp. S1117–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.1352.

- Pillarisetty LS, Bragg BN. Late Decelerations. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539820.

- Schifrin, Barry S., et al. “Approaches to Preventing Intrapartum Fetal Injury.” Frontiers in Pediatrics, vol. 10, Sept. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.915344.

Learn to distinguish between an evaporation line and a faint positive pregnancy test. Discover 3 key differences and tips for accurate results. Expert insights from Femia.

Learn how soon after sex should you take a pregnancy test. Discover the best timing for a pregnancy test after sex. Expert tips and advice. Get all the answers on Femia.

Considering using Mucinex to help you get pregnant? Find out whether the Mucinex pregnancy trick is fact or fiction, how to use it, and who should stay away.